I updated this post after some constructive feedback, though now its a longer, yet more complete, piece – July 18th,

Are you ready for Round 2? Well before I reveal what policy makers aren’t telling you, let me first reiterate what they are telling you. Here’s a list of quotes that summarize the opinions of the chattering class as it pertains to climate change.

Are you ready for Round 2? Well before I reveal what policy makers aren’t telling you, let me first reiterate what they are telling you. Here’s a list of quotes that summarize the opinions of the chattering class as it pertains to climate change.

“We should reframe our response to climate change as an imperative for growth rather than merely being a way of being green or meeting environmental commitments.” – William Hague, Former British MP & Leader of the House of Commons

“Warming should not exceed 2 °C… [however], it is possible to stick to this limit by introducing measures to cut emissions that only cause an annual 0.06 percentage point cut in … economic growth” – The Financial Times, 2014

“Houston has proven that it can maintain its title as the energy capital of the world while at the same time pursuing green policies… but we must continue to reduce greenhouse gas emissions…This is not only good for the health of our residents… but we know it also improves our economic performance and growth.” – Annise Parker, Former Mayor of Houston

“The amount of… ‘churn’ or job destruction and job creation linked to climate mitigation is expected to [be] about 0.5% of total employment – quite small compared with the overall ‘churn’ that normally occurs in a market economy.” – The New Climate Economy Report 2014

“We now know that climate action does not require economic sacrifice… [it] is up to all of us to make smart policy choices that will help combat climate change.” – Sri Mulyani Indrawati, Former Managing Director and Chief Operating Officer of the World Bank

All of these statements paint a similar picture. While the fight against climate change won’t be easy, committing ourselves to finding a solution will save the planet for future generations while not significantly affecting the global economy or our current standard of living. In fact, this is a view that I (until recently) championed myself, and for good reason.

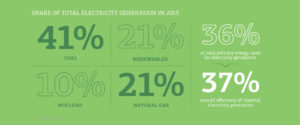

A recent report conducted by Environmental Entrepreneurs estimated that there were 3 million clean energy and transportation jobs in the U.S. in 2016. Additionally, since 2006 the U.S. has installed nearly 36 GW of solar capacity (combining residential & utility installation). By the way, just as a point of reference, there was essentially no installed solar capacity in the U.S. before 2006. In fact, the compounded annual growth rate (CAGR; a measurement of annual growth that can be used to compare investments across different industries) for American made photovoltaics (60%) nearly doubled the CAGR of smartphones made worldwide. Investments in wind & solar outpace investments in coal & natural gas by approximately 2 to 1. And as of 2013 global electricity generation from renewables matched that of natural gas according to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) 2016 report tracking clean energy progress.

So the growth of the clean energy sector has been more than encouraging, but as I illustrated in my last post what matters most isn’t the growth of renewables (though the expedited growth of clean energy capacity is absolutely vital) it’s the capping of CO2 emissions. It’s great that renewables account for nearly 25% of electricity generation globally, but over 75% of global emissions originate from sectors other than electricity generation. That includes transportation, industrial processes, deforestation, agriculture, and many more.

All energy produced from all sectors must emit net-zero greenhouse gas emissions before we blow our carbon budget. That is what it means to “solve” the civilization-threatening problem of climate change. So let me detail for you, as promised, the full-scale view of the climate crisis, a view that our policymakers & national media outlets are neglecting to make clear to the public.

In 2015 Kevin Anderson, the Deputy Director of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, performed a straightforward analysis, using simple algebra, to calculate the rate at which we, humanity, have to reduce CO2 emissions in order to avoid dangerous climate change Failure to do so, by the way, will result in the deaths of hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people (we always have to keep that fact in mind). Now sit tight, because Prof. Anderson’s analysis paints a very bleak picture for progress. However, I have to provide some context first. The Paris climate talks during late 2015 established this aim for the international community:

[Hold] the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and… pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C… [in recognition] that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change

So to start off, Anderson took the IPCC’s (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) carbon budgets for a 1.5 & 2 °C global temperature increase and calculated how many tonnes of carbon emissions we have left to “spend” or emit into the atmosphere. For, example the carbon budget for an outside (33%) chance of avoiding a 2 °C rise in average global temperature is 1500 billion tonnes (1500 Gt) of CO2 emitted between the years 2011 & 2100. Simply by updating this budget to account for the CO2 that has already been emitted or “spent” since 2011, (which was 140 GT at the time his report was written in 2015) you’ll find that society has 1340 Gt of CO2 left to emit or “spend,” as of 2015, before it becomes essentially impossible to halt a 2 °C temperature increase.

Next Anderson incorporated the current growth projections for the three sources primarily responsible for CO2 emissions, energy consumption, deforestation, and (oddly enough) cement production, into his budget analysis; the professor then uses this information to calculate (in tonnes of CO2 per annum or p.a.) how rapidly society, as a whole, has to decarbonize in order to avoid dangerous climate change. (Note: reductions per annum are annual reductions based on the previous year’s total i.e. the total percentage reduced each year; so the total amount reduced annually gets smaller over time)

For a full overview on how Anderson incorporates these projections and performs his analysis, I would encourage you to read his report published in Nature Geoscience, Duality in climate science, or watch one of the many lectures he has posted regarding this subject on YouTube. But to be brief, Anderson essentially weds his analysis to another aim of the Paris Agreement which mandates that the nations signing on to the accord promise to address the long-term consequences of increasing greenhouse gas emissions “on the basis of equity, and in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty.” In layman’s terms, this means that developing countries, struggling to feed their people and grow economically, will be more reliant on fossil fuels, as well as other carbon-intensive technologies, in the short term. Thus they must be allowed to peak their CO2 emissions at a later date and decarbonize at a slower pace; as opposed to rich & developed countries, like the US, who should be asked to do more and peak their emissions as soon as possible.

So, what did Prof. Anderson find out? How quickly do we have to reduce CO2 emissions? Well first let’s start with the good news.

As luck would have it, China dominates the CO2 emissions produced by developing countries so effectively when China peaks its emissions we can reasonably assume the entirety of the developing world has peaked its emissions, in aggregate (and yes that assumption takes into account the emissions from India, which surprised me).

Anderson postulates that CO2 emissions from the developing world must peak by 2025, so a Chinese emissions peak by 2025 will essentially accomplish this. Well as it turns out, a 2025 emissions peak is not as unreasonable as it sounds. China has already vowed to peak their emissions by around 2030 and an independent report commissioned by the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment shows that an emissions peak in 2025 is not only feasible but likely. This is truly fantastic. However, here comes the bad news.

Without relying on any geo-engineering hocus pocus, in order to stay within the carbon budget for an outside chance of avoiding a 2 °C global temperature rise the developing nations must then reduce their net emissions each year thereafter and ultimately reach a reduction rate of 10% p.a. by 2035, fully decarbonizing by 2050. There are currently no plans in the works to reach emission reduction rates even approaching this and in fact, the Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change argues that emission reduction rates of 3% p.a. or more are likely not consistent with economic growth.

For reference, the impressive ramp up of nuclear power by the French during the 1970s only reduced carbon emissions by around 1% p.a., according to the Stern Review. For comparison, Russia’s emissions rate dropped by approximately 5.4% p.a. between 1989 & 1998 in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union (which was obviously not a time of economic prosperity).

Now, there have been new studies published since the commission of the Stern Review in 2006 that show evidence of a decoupling of economic growth from carbon dioxide emissions. Most prominently, an International Energy Agency (IEA) report found that global CO2 emissions from energy-related activities remained constant between 2013 & 2016 while global GDP grew by more 3%. However, the IEA readily admits that if the economy grew faster emissions would invariably have risen (remember society was still recovering from impacts of the Great Recession).

Additionally, this reported “decoupling” ignores the fact that our economy is still heavily reliant on fossil fuels and deep decarbonization remains an immense challenge. So reducing emissions at rates approaching 5-10% p.a. poses real risks of economic stagnation (at least until clean energy and carbon-neutral technologies become cheap and easily accessible).

The picture doesn’t get any rosier when you move on to address the developed nations; in fact, the implications are even more dire. Assuming again that the poorer countries peak their CO2 emissions in 2025, in order to stay within our carbon budget for an outside chance at 2 °C, Anderson calculated that the developed nations have to completely decarbonize by 2035.

Yes not 2100, or even 2050, the U.S. economy, as well as the economies of France, Germany, and all the other wealthy nations, must operate on net-zero emissions in less than two decades. In order to achieve such a feat the developed countries, according to Anderson’s analysis, must reduce their emissions at a rate of 10% p.a., starting…. NOW! TODAY! Or preferably back in December 2015, when Anderson’s report first was released.

I should also point out that since we took the last year or so dilly-dallying that reduction rate has likely increased to more than 12% p.a. And, just as for the developing nations, an emission reduction strategy this aggressive is most likely not consistent with sustained economic growth. Cuts this deep and this sudden outpace our capacity to reduce emissions simply by shifting energy supply from fossil fuels to renewables, even without considering the political constraints.

So in the short-term sharp reductions in energy demand, and thus overall consumption, are required (i.e. less driving, less electricity use, less meat consumption, etc). Efforts to sequestration carbon will alleviate some of these burdens, but carbon sequestration is by no means a panacea.

Now the technological progress the green energy sector has made is truly astounding and believe it or not, the innovative solutions social entrepreneurs are concocting genuinely give me hope for the future. (pick up a copy of Project Drawdown if you want some reality-based optimism) All that being said, deep and rapid decarbonization simply is not a recipe for booming financial markets.

So given all of that, how can it be that policymakers (and even many scientists) are out there as we speak making statements applauding the potential for green growth and the great economic “opportunity” that the climate crisis has handed us. Are they unaware of these finding? Do they dispute this analysis or the concept of carbon budgets? Are they purposely trying to deceive the public?

Well, I believe the answers to those questions, especially the last two, are no. So what’s actually going on? Well, to be frank, politics are to blame (and capitalism to an extent). The modern capitalist system has been built on the tenant that the economy of the future must be larger than the economy of the past for society to thrive & prosper; abiding by this tenant, most politicians have prioritized economic growth above almost all other things. This “growth imperative” as it’s called may or may not be real or necessary, but in a world where it is taken as economic law, any legislation that negatively affects economic growth is DOA, dead on arrival.

So instead of building climate policy upon the unforgiving reality of carbon budgets our lawmakers, and the academics that work alongside them, frame all policy through this current economic paradigm that society has deemed infallible. This paradigm doesn’t only dictate how legislation is written, but which projects get federally funded, what types of research are awarded government grants, and whose opinions get taken seriously by are our elected leaders. This overwhelming political pressure has lead to denialism, procrastination, and irresponsible policy-making by our world’s governments.

By the way, speaking of irresponsible policy-making, exactly how are lawmakers dealing with the reality that we are quickly running out of time to halt the onset of dangerous climate change. Well luckily for them (and unluckily for the future of human civilization) geo-engineering, and the concept of “negative emissions” more generally, has squared that circle. Now they say that the perfect length for a blog post is 1600 words and this one is rapidly approaching 2000, so we’ll get into the “hocus pocus” they call geoengineering (and the over-reliance on negative emissions pathways) next week in part 2 of What Policymakers Aren’t Telling You About the State of Climate Change.